What if we used our waterways for transport?

Back in January before the COVID19 pandemic I rode my bike from work to UP Diliman to have drinks with my wife and friends. Rather than take the main roads such as EDSA or C-5, I crossed the River using an informal, makeshift ferry service and continued my way until I arrived at my destination. Using the main roads clogged with motorized traffic would have cost me an hour two, while commuting or riding Grab would have cost me 500 Php AND 3 hours. Crossing that river set-off a year-long musing: why don’t we use our rivers more for transport?

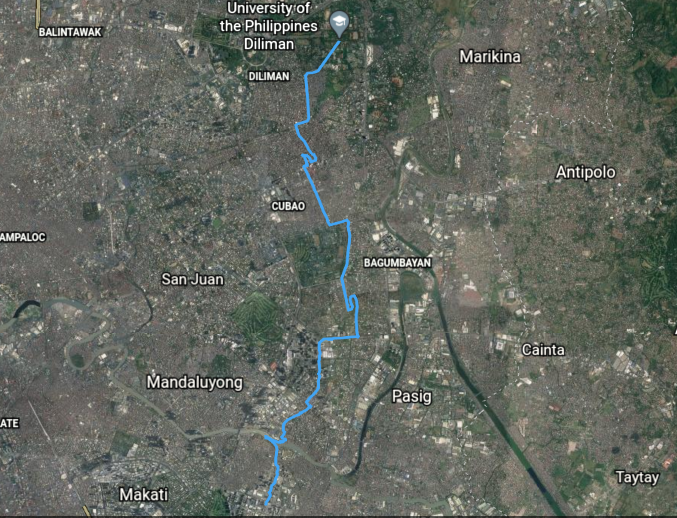

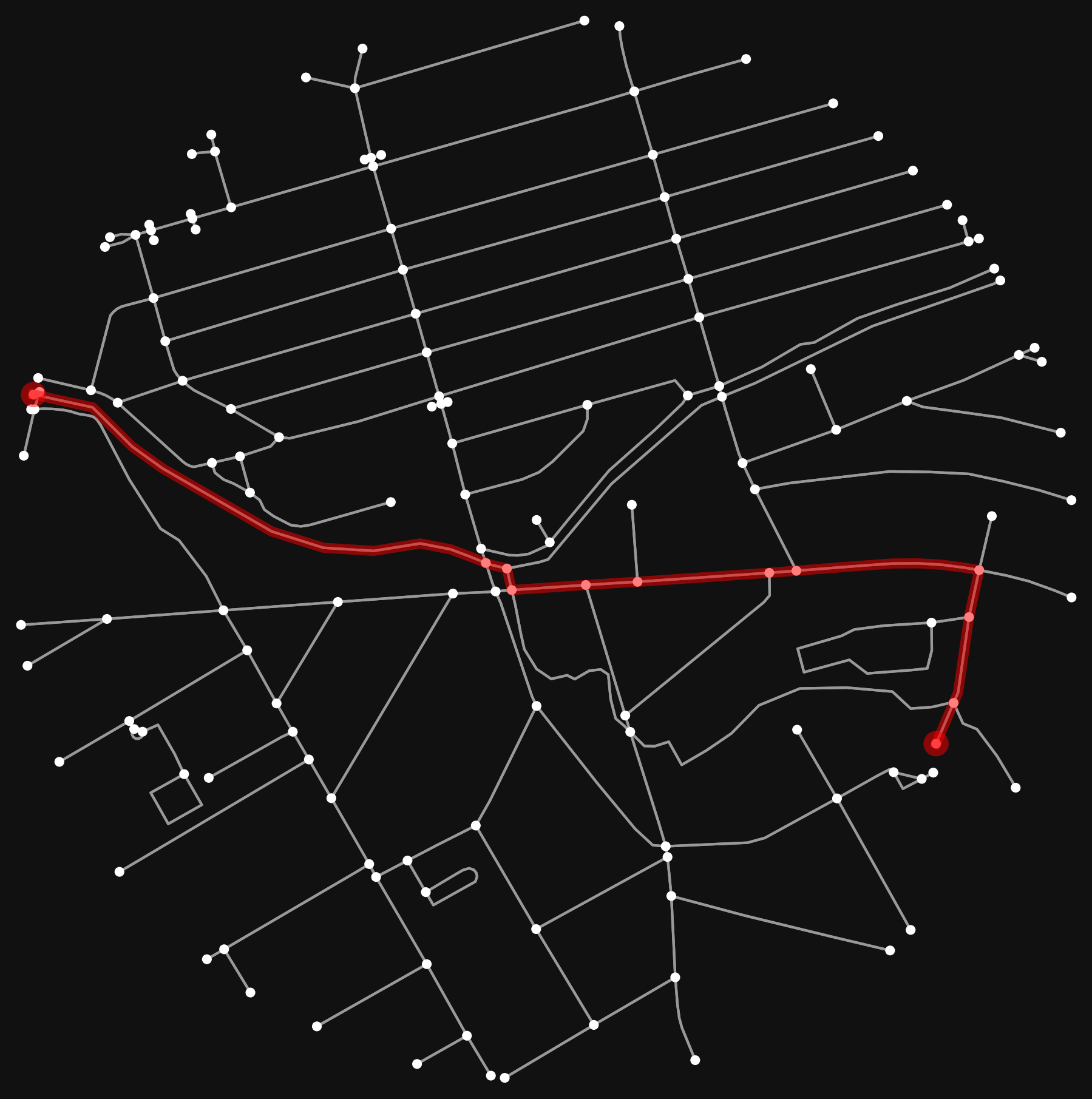

After-work bike route I logged last January

One of my most memorable after-work bike commutes before everything of 2020. Take note of my Pasig river-crossing at the first 5 kilometers of my route from Bonifacio Global City at the lower half of the image.

There is an abundance of free and open-source data and technology that we can use to reimagine our routes that use both the road and waterway network. Think of Waze or Google Maps but using the esteros, canals, rivers and spillways as segments of routes if they were made usable. These apps use routing algorithms to recommend to users the best path from origin to destination. However, they are primarily catered to motorists and therefore only consider the road network that motorized transport may use.

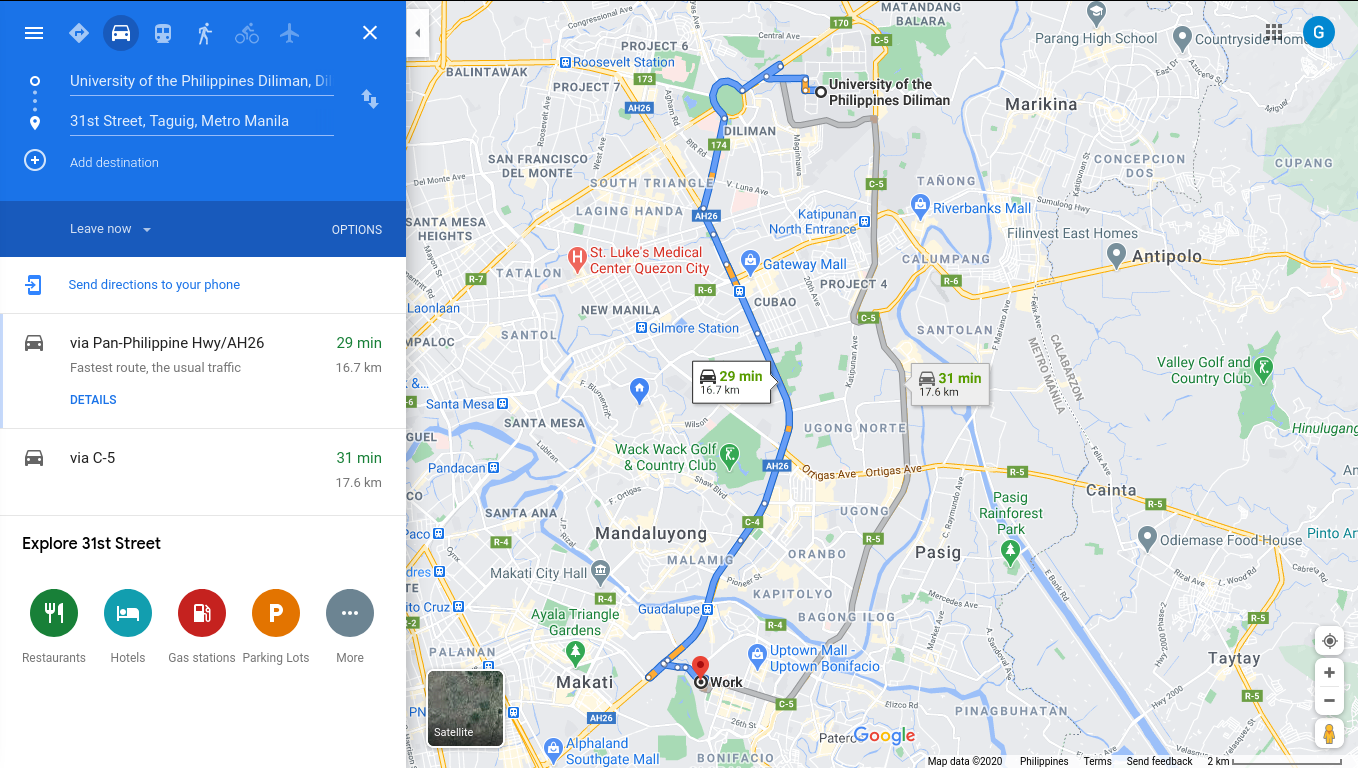

Suggested route by Google Maps

The service primarily suggests routes for motorized transport. The only viable routes are EDSA or C5, both of which are congested and take about 2-3 hours to traverse during rush hours.

We have the Pasig River Ferry service, but they don’t operate at a scale that would serve the commuting public at large. As a bike commuter, our waterways provide a viable alternative for bimodal transport across the city.

Our Thai neighbors appear to have the right idea in using their local geography and natural waterways as part of getting around the city. What if we, at least in maps, re-imagine what our routes would look like if we could use Metro Manila’s waterways as part of our transportation system?

Reimagining Our Routes . . .

Waze or Google Maps or other routing apps are constrained by programming to use the road network only to suggest routes. The intent of all this effort is to see if we can fool and reprogram routing algorithms to take the road and street network together with the waterway network to suggest routes. To simulate this hypothetical scenario, the road network and waterways needed to be represented as one network. Both are currently represented as separate entities so the trick is to process the data to fool routing algorithms as if they were one network.

To keep things simple I picked a location that I could easily bike to and had waterways that criss-crossed the road network.

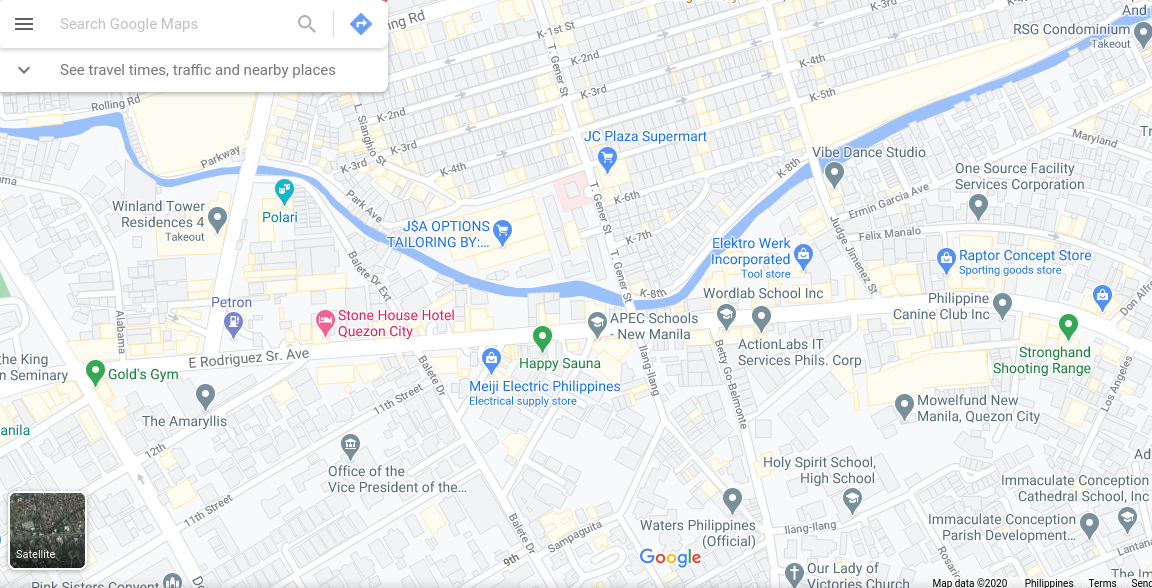

Google Map of the sample study area

Diliman Creek snakes horizontally across the picture clearly creating a natural boundary between the residential and commercial areas. Click on the image to explore the location in Google Maps

One of the intriguing take-aways from my initial mapping activity of the area was how unrepresented some of waterways are in commercial maps. Compare the Google Map of the area and the Openstreetmap and you’ll notice the absence of the stream in Google maps. This merits a separate write-up as it will deviate from the main agenda of this post.

. . . By Fooling Algorithms

Navigation is a fascinating subject, even moreso in science fiction such as Dune. The development of digital maps and navigation apps has simplified much of the work needed to figure our way around spaces and places. However, like any other forms of algorithms they have their limitations and as I alluded earlier, most navigation and mapping apps were developed for motorized transportation in mind.

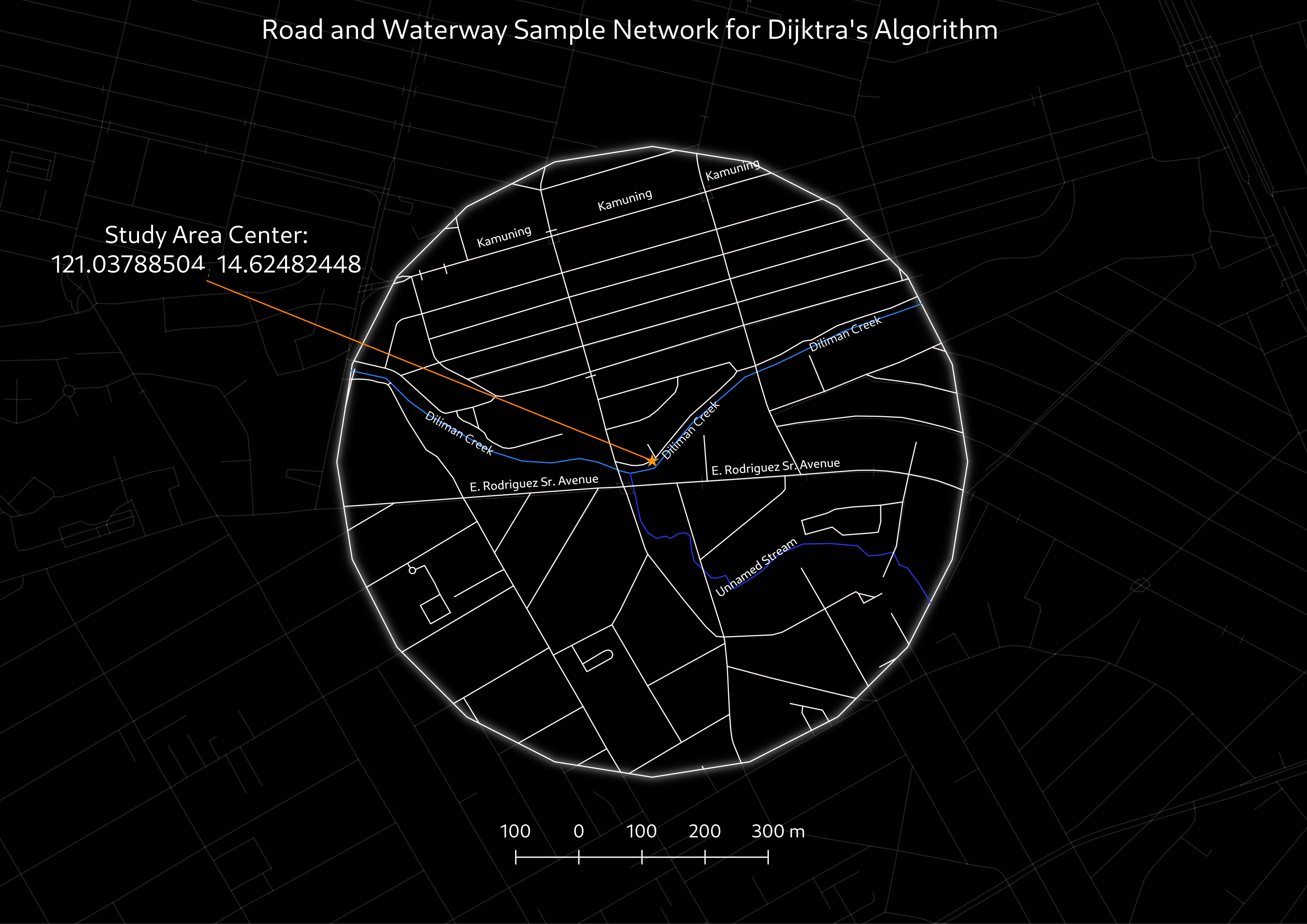

Road and waterway network of the study area using Openstreetmap data

Take note of the unnamed stream in the data that’s barely visible in the Google Map screenshot. Click on the image to explore the location in Openstreetmap.

Algorithms are dumb and much of the technical work is in manually manipulating the map data to merge the road and water network. This merged network then is fed into Dijkstra’s (pronounced as Dike-stra) algorithm that computes the shortest path between two locations. For a more nerdy take on this process you may read the technical note that breaks down the general steps and technical challeges in processing the data.

Fooling Dijkstra's Algorithm

Using the algorithm use Diliman Creek and E. Rodriguez Sr. Ave. as inputs for shortest-path sample route between a random pair origin and destination points. The red path is the shortest path out of all possible paths determined by Dijkstra’s algorithm.

All this may not seem much now, but it’s a pretty big deal if we were to scale-up this simulation for Metro Manila. Imagine the time and money we could have collectively saved we were able to use the Pasig and Marikina Rivers and the feeder waterways as part of our routes across the city. We already have an idea of the slow travel speeds of motorized transport during congested peak-hours. All it would take is a few input parameters to have at least a workable estimate of how more effective it would be to travel using the water network instead of spending so much on building and maintaining complex infrastructure.